Medication Risk Checker for Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Identify Potential Medication Risks

This tool helps you understand if your medications could increase risk of acute angle-closure glaucoma. Select any medications you're currently taking or have taken recently.

Risk Assessment Results

Select medications to see your risk assessment.

Imagine waking up with a pounding eye pain, a halo of lights around every streetlamp, and nausea that won’t quit. Within minutes the world starts to blur and you’re suddenly terrified you might go blind. That nightmare is exactly what happens in a acute angle‑closure glaucoma attack sparked by a medication. It’s a medical emergency that demands immediate action-delay even an hour and the optic nerve can suffer permanent damage.

What is acute angle‑closure glaucoma?

Acute Angle‑Closure Glaucoma is a sudden blockage of the eye’s drainage angle that spikes intraocular pressure and can cause rapid vision loss. The drainage angle, formed where the iris meets the cornea, normally lets aqueous humor flow out of the eye. When that angle closes, pressure climbs fast-often beyond 40 mm Hg-and the optic nerve begins to starve for blood.

How do medications turn a quiet eye into a ticking bomb?

Only a few drug classes have the power to force the angle shut, but they’re surprisingly common. The key is the eye’s anatomy: people with narrow iridocorneal angles, short axial length, or high hypermetropia are sitting on a pressure cooker. When a trigger drug dilates the pupil or swells the iris, the already‑tight space snaps shut.

The three mechanisms are:

- Pupillary block - most drugs cause the pupil to dilate, pulling the peripheral iris against the lens and sealing the flow path.

- Plateau‑iris configuration - the ciliary body is positioned forward; a medication‑induced iris thickening completes the closure.

- Malignant (or secondary) glaucoma - swelling of the ciliary body pushes the lens‑iris diaphragm forward, narrowing the angle further.

High‑risk medication classes (and why they matter)

| Class | Typical agents | Risk % of AACG cases | Primary mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

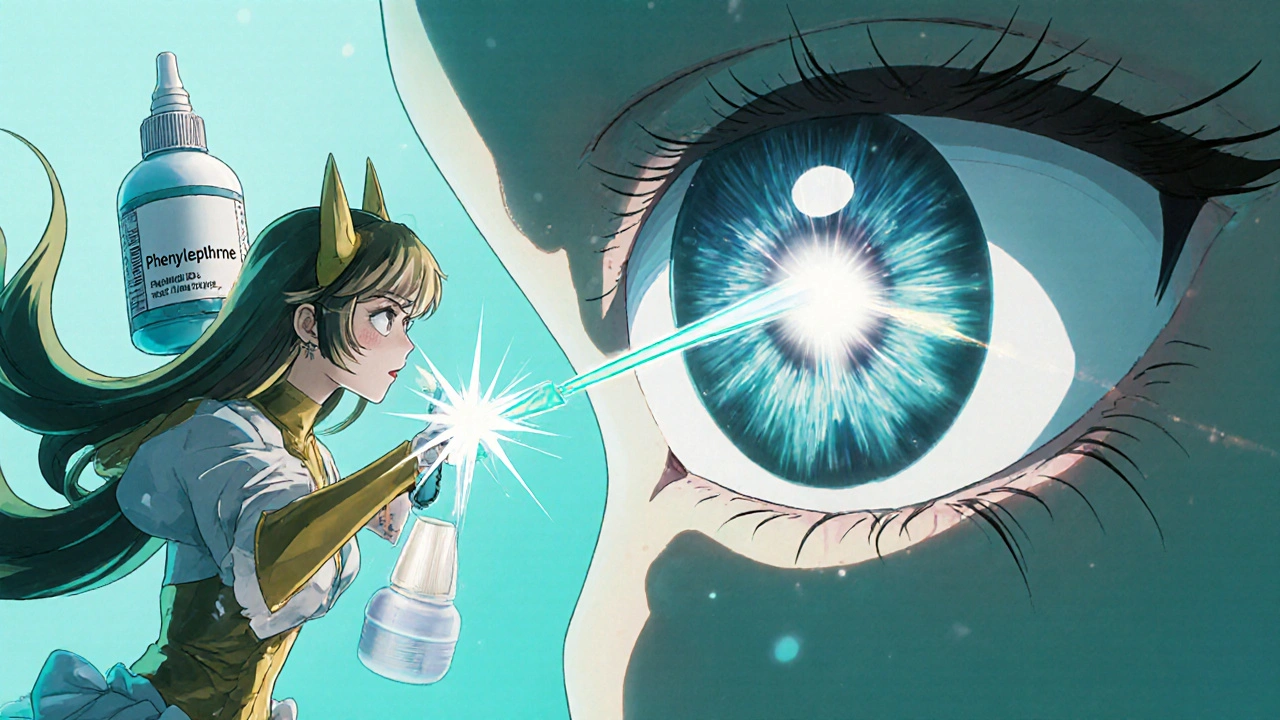

| Adrenergic agents | Phenylephrine (10 % eye drops), ephedrine | 35 % | Pupillary dilation |

| Anticholinergics | Tropicamide (1 % drops), atropine | 28 % | Iris swelling + dilation |

| Sulfonamides | Acetazolamide, topiramate | 15 % | Ciliary body edema |

| SSRIs | Paroxetine, fluoxetine | 12 % | Sympathetic over‑activity → dilation |

| Antihistamine/decongestants | Diphenhydramine, pseudoephedrine | 10 % | Pupillary block |

Spot the warning signs-what patients feel and see

Most attacks present with a classic cluster of symptoms:

- Severe, unilateral eye pain that may radiate to the forehead or jaw.

- Sudden blurred vision with halos around lights.

- Red, injected conjunctiva ("bloodshot" eye).

- A mid‑dilated, fixed pupil (typically 4‑6 mm).

- Headache, nausea, and even vomiting.

If you or someone you know has taken a high‑risk drug and experiences any of these within 24 hours, call emergency services immediately. The window for saving vision is narrow- optical nerve fibers can be irreversibly damaged after just 6‑12 hours of pressure above 40 mm Hg.

How doctors confirm the diagnosis

Rapid assessment in the ER or ophthalmology clinic involves three core steps:

- Measure intraocular pressure (IOP). Using a Goldmann applanation tonometer, a pressure reading above 30 mm Hg is highly suggestive of AACG.

- Gonioscopy is performed to directly view the angle and verify that it is indeed closed. A Shaffer grading of ≤2 confirms a narrow or closed angle.

- Slit‑lamp examination reveals corneal edema, a shallow anterior chamber, and the characteristic mid‑dilated pupil.

Sometimes ultra‑wide OCT (optical coherence tomography) is used for a quick, non‑contact angle assessment. OCT has shown a 94 % sensitivity for detecting narrow angles, making it a valuable screening adjunct.

Emergency treatment - what happens in the first 24 hours

The goal is to lower IOP fast, break the pupillary block, and create a permanent opening in the angle.

- Pilocarpine 2 % drops are administered every 15 minutes for the first hour to constrict the pupil and pull the iris away from the lens.

- Systemic osmotic agents such as Intravenous Mannitol (1‑2 g/kg) rapidly draw fluid from the eye, further dropping pressure.

- Topical β‑blockers (timolol) and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (brinzolamide) are added to block aqueous production.

- Within 24 hours, Laser Peripheral Iridotomy is performed. A tiny hole in the peripheral iris lets fluid bypass the blockage, permanently equalizing pressure.

Even after pressure normalizes, patients stay under observation for at least 48 hours because rebound spikes can occur, especially if the offending drug is still in the system.

Preventing a drug‑induced crisis - screening before prescribing

Prevention is far cheaper-and less painful-than emergency care. The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends a simple protocol for any adult over 40 who will receive a high‑risk drug:

- Ask about a personal or family history of glaucoma.

- Perform a quick Gonioscopy (5‑7 minutes per eye). If the angle is narrow (Shaffer ≤2), note it in the chart.

- Document the risk in the electronic health record. Modern EHRs like Epic flag high‑risk prescriptions automatically.

- Choose safer alternatives: replace phenylephrine nasal sprays with saline, use loratadine instead of diphenhydramine, or select a β‑2 agonist for asthma rather than epinephrine.

If a patient already has a known narrow angle, the safest move is to avoid all drugs with anticholinergic or strong adrenergic properties unless absolutely necessary.

Real‑world stories that highlight the gaps

On a popular glaucoma forum, a user named "VisionWarrior42" described taking pseudoephedrine for a cold, then developing unbearable eye pain. He was first sent home with migraine medication, and by the time AACG was diagnosed he’d already lost 20 % of peripheral vision. Another Reddit post detailed a routine eye‑exam where the optometrist used tropicamide drops without a prior angle check-resulting in an IOP of 60 mm Hg and permanent visual field loss.

These anecdotes echo data from the BrightFocus 2022 patient survey: 18 % of glaucoma patients reported medication‑related complications, with an average diagnosis delay of 17 hours. The same study found that 78 % of affected patients were never warned about eye risks when the drug was prescribed.

Future directions - technology and genetics

Newer imaging tools are closing the screening gap. Anterior segment OCT can map angle width in seconds, and artificial‑intelligence algorithms are being trained to flag eyes that need gonioscopy. On the genetics front, the GLAUGEN Consortium identified 17 markers linked to narrow angles, opening the door for a simple blood test that could predict susceptibility before any eye exam.

Even with these advances, a 2023 AOA survey showed only 42 % of primary‑care physicians routinely screen before prescribing high‑risk drugs. Education modules targeting non‑ophthalmologists have been rolled out, but adoption remains uneven.

Quick checklist for clinicians

- Identify high‑risk drug classes (adrenergic, anticholinergic, sulfonamide, SSRI, antihistamine).

- Screen patients >40 y/o with gonioscopy or anterior‑segment OCT.

- Document angle status in the EHR and trigger alerts for future prescriptions.

- Choose safer alternatives whenever possible.

- If AACG develops, start pilocarpine, mannitol, and arrange laser iridotomy within 24 h.

- Monitor IOP for at least 48 h post‑procedure.

Bottom line

Medication‑induced acute angle‑closure glaucoma is a preventable yet deadly eye emergency. Knowing the culprits, recognizing the warning signs, and applying a rapid treatment algorithm can save sight. Equally important is a proactive screening culture-if you’re a prescriber, a quick gonioscopy or OCT before you write that nasal decongestant could be the difference between a patient seeing clearly for life or living with permanent vision loss.

What symptoms should prompt an emergency visit?

Sudden severe eye pain, a mid‑dilated fixed pupil, red eye, halos around lights, nausea, and blurry vision are classic signs. Seek care within the hour.

Which common over‑the‑counter products can trigger AACG?

Phenylephrine nasal sprays, pseudoephedrine decongestants, diphenhydramine antihistamines, and certain eye‑drops like tropicamide are frequent offenders.

Can a person with normal eyes develop drug‑induced AACG?

It’s rare. The condition almost always occurs in eyes that already have a narrow iridocorneal angle or a short axial length.

How long does it take for pressure to fall after treatment?

With aggressive therapy-pilocarpine, mannitol, and laser iridotomy-IOP often drops below 20 mm Hg within a few hours, but observation continues for 48 hours.

Is there a genetic test for narrow angles?

Research labs now offer panels that include the 17 GLAUGEN markers, but routine clinical use is still limited to high‑risk families.

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

HILDA GONZALEZ SARAVIA

October 24, 2025 AT 15:33Screening before prescribing high‑risk meds is absolutely essential. A quick gonioscopy or an anterior‑segment OCT can spot a narrow angle in under five minutes. Most clinicians overlook this step because they assume the patient has “normal” eyes. The data in the post shows that nearly half of acute attacks could be prevented with a simple exam. Documenting the angle status in the electronic health record also creates an automatic alert for future prescriptions. In practice, having a checklist on the prescribing workflow saves both time and vision.

Amanda Vallery

October 24, 2025 AT 21:06Obviously the sulfonamides r the worst and doctors shuld know that.

Marilyn Pientka

October 25, 2025 AT 05:26From a pharmacovigilance standpoint, the iatrogenic cascade precipitated by adrenergic agonists epitomizes a failure of translational risk assessment. The etiologic nexus between pupillary block and systemic sympathomimetic exposure is incontrovertible, yet prescribing algorithms remain obstinately antiquated. Such negligence not only contravenes the principle of non‑maleficence but also erodes the epistemic integrity of ophthalmic stewardship. In lay terms, we are handing patients a ticking time‑bomb for the price of a nasal spray.

Kathryn Rude

October 25, 2025 AT 12:23One might argue that the very act of prescribing without angle‑assessment reflects a deeper philosophical malaise of our healthcare system an over‑reliance on convenience over caution it's a tragicomic tableau where the patient becomes a sacrificial lamb for the sake of expediency :)

Lindy Hadebe

October 25, 2025 AT 23:30Another example of systemic oversight that could have been avoided with a simple precaution.

Ekeh Lynda

October 26, 2025 AT 12:23Acute angle‑closure glaucoma triggered by medication is a preventable catastrophe.

The prevalence of narrow angles in the aging population is well documented.

Yet clinicians often dispense high‑risk agents without a prior ocular assessment.

The pharmacodynamics of adrenergic and anticholinergic drugs predispose susceptible eyes to pupillary block.

When the iris bows forward the aqueous humor outflow is abruptly halted.

Intraocular pressure can surge beyond forty millimetres of mercury within minutes.

Visual field loss becomes irreversible after a few hours of sustained elevation.

Screening modalities such as gonioscopy and anterior‑segment OCT are inexpensive and rapid.

Electronic health records can be programmed to flag high‑risk prescriptions automatically.

Patient education about warning signs like halos and severe pain is equally vital.

Case reports continue to emerge where delayed diagnosis resulted in permanent vision loss.

Healthcare systems should institutionalize mandatory angle evaluation before dispensing relevant drugs.

Such protocols would align clinical practice with the ethical imperative to do no harm.

Moreover, interdisciplinary communication between primary care and ophthalmology can bridge existing gaps.

Ultimately, the burden of preventable blindness rests on collective vigilance rather than isolated interventions.

Kester Strahan

October 26, 2025 AT 20:43Spot on – the lack of a quick gonioscopy is a glaring oversight. In my clinic we’ve integrated a handheld OCT that adds only a minute to the workflow and has already caught several at‑risk eyes before a prescription was written. Happy to share the protocol if anyone’s interested.

Jordan Levine

October 27, 2025 AT 06:26THIS IS HUGE!!! 😱 A simple nasal spray turning someone’s world into darkness is an outrage that should ignite a national debate on drug safety! 🚨 We can’t let pharma get away with this any longer!!

Carla Taylor

October 27, 2025 AT 12:00Let’s channel that energy into constructive change – education campaigns, better screening, and patient advocacy can make a real difference 😊

Mary Mundane

October 27, 2025 AT 18:56Screening saves sight.

Michelle Capes

October 27, 2025 AT 23:06Totally agree! Even a quick check can prevent a lot of pain and loss 😊

Dahmir Dennis

October 28, 2025 AT 07:26Oh, brilliant, another reminder that “we should have known better” after the fact. The medical community loves to lecture on hindsight while continuing to prescribe blindly. It’s almost as if profit margins trump patient safety in every board meeting. One would think that after decades of research, we’ve mastered basic risk assessment. Yet here we are, watching avoidable blindness unfold because a doctor thought a decongestant was harmless. Perhaps the next step is to require a PhD in ophthalmology before anyone can buy over‑the‑counter medication. The irony is not lost on anyone paying the price for such negligence. Let’s hope the next guideline actually gets read.