Every year, thousands of seniors with dementia are given antipsychotic drugs to calm agitation, aggression, or hallucinations. It seems like a quick fix - until a stroke happens. Or worse, until they don’t wake up. The truth? These medications aren’t just risky. For many older adults, they’re deadly. And yet, they’re still prescribed - often without a full conversation about what’s really at stake.

Why Are Antipsychotics Even Used in Dementia?

Dementia isn’t just memory loss. It can bring out behaviors that are hard to manage: pacing all night, yelling, hitting, or believing people are stealing from them. Families and caregivers are exhausted. Nursing homes are understaffed. In that pressure, antipsychotics become the easiest tool in the box. But here’s the catch: these drugs were never designed for dementia. They were made for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. When used in seniors with dementia, they don’t fix the root problem - they silence the person. And the cost? A much higher chance of stroke, heart attack, or sudden death.The FDA Warning No One Talks About

In 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration put a black box warning on all antipsychotic medications - the strongest warning they can give. It said clearly: elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis who take these drugs have a 1.6 to 1.7 times higher risk of death than those who don’t. That’s not a small risk. That’s nearly double. And it’s not just from long-term use. Even a few weeks on these drugs can be dangerous. A 2012 study of U.S. veterans found that stroke risk jumped by 80% after just short-term exposure. That’s not a side effect - it’s a direct consequence.Typical vs. Atypical: Does One Cause Less Harm?

Doctors often say, “We switched you from the old drug to the newer one - it’s safer.” But the data doesn’t back that up. First-generation antipsychotics (like haloperidol) are older, cheaper, and known to cause more movement problems. Second-generation ones (like risperidone, quetiapine) are marketed as gentler. But here’s what the research shows:- Both types increase stroke risk equally in the short term.

- Long-term use of first-generation drugs carries a higher risk of cerebrovascular events than second-generation ones.

- But second-generation drugs aren’t harmless. They raise the risk of diabetes, weight gain, and metabolic syndrome - which also increase stroke risk over time.

How Do These Drugs Cause Strokes?

It’s not magic. It’s physiology. Antipsychotics block dopamine and serotonin in the brain. That’s how they calm agitation. But they also mess with blood pressure control. Many seniors on these drugs develop orthostatic hypotension - a sudden drop in blood pressure when standing up. That’s a direct path to a stroke. They also trigger metabolic changes: higher blood sugar, more belly fat, worse cholesterol. These are all stroke risk factors. And in someone already aging with dementia, their body can’t compensate. A small dip in blood flow becomes a clot. A small clot becomes a stroke. And here’s the hidden danger: cognitive decline might not be just from dementia. It might be from tiny, silent strokes caused by the medication itself. The worse the behavior gets, the more drugs are given - creating a vicious cycle.

Real Numbers, Real People

In 2005, researchers in Canada looked at over 32,000 seniors with dementia. Half were on antipsychotics. The other half weren’t. The stroke rates? Nearly identical between those on first-gen and second-gen drugs. That means the “safer” option wasn’t safer at all. Another study of nearly 5,000 nursing home residents found that those on antipsychotics were far more likely to be hospitalized for stroke or TIA. And the risk didn’t go down after a few months - it kept climbing. These aren’t rare cases. They’re predictable outcomes. In the U.S., over 1 million seniors with dementia are on antipsychotics. About 1 in 5 will have a stroke or die within a year of starting the drug. That’s not an accident. It’s a pattern.What Do the Experts Say?

The American Geriatrics Society says it plainly in their Beers Criteria: Do not use antipsychotics for behavioral symptoms of dementia. They’ve said it since 2015. And they’re not alone. The American Heart Association says: Antipsychotic therapy should only be considered after non-drug approaches have been tried - and even then, only for the shortest time possible. And yet, in nursing homes across Canada and the U.S., these drugs are still handed out like candy. Why? Because staff are overwhelmed. Because families are desperate. Because no one knows what else to do.What Works Better Than Drugs?

There are proven, safer ways to manage behavioral symptoms - if you have the time and support.- Environmental changes: Reduce noise, improve lighting, create quiet spaces. Overstimulation triggers aggression.

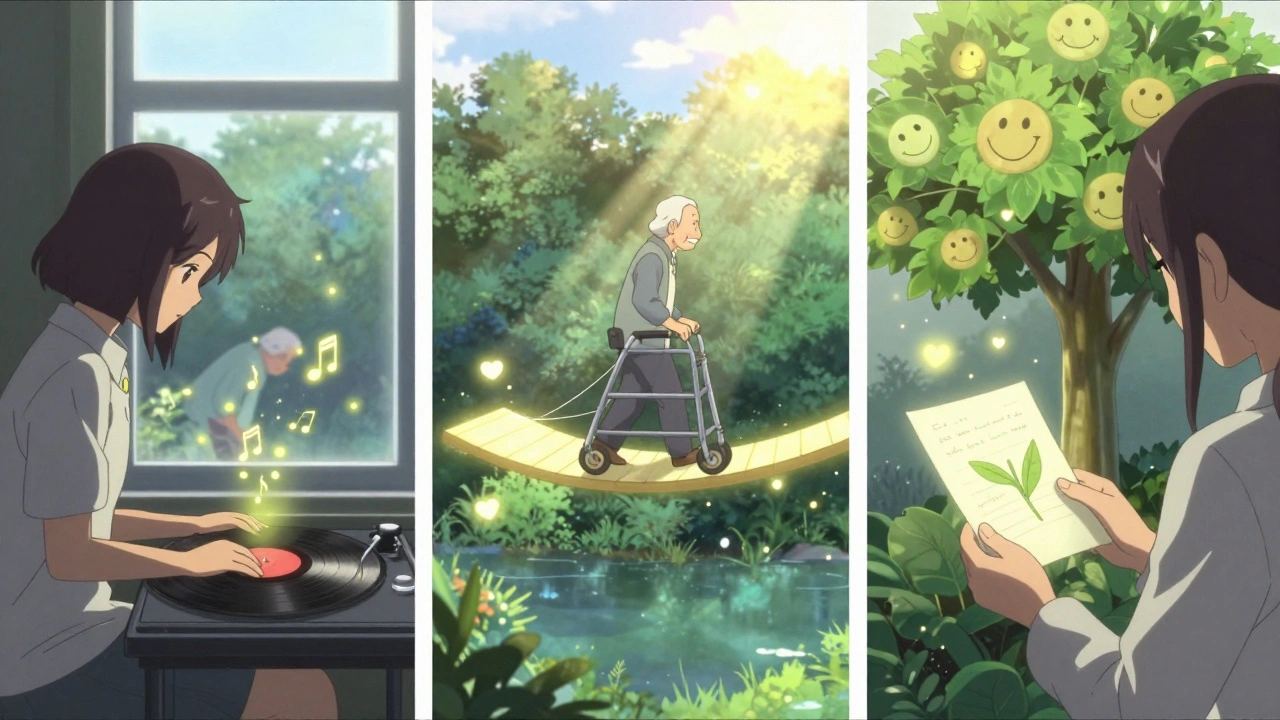

- Person-centered care: Understand the person’s history. Were they a musician? Play their favorite songs. Were they a teacher? Give them simple tasks that feel meaningful.

- Schedule consistency: Dementia thrives on routine. Unpredictable meals or baths cause anxiety.

- Staff training: Caregivers who learn de-escalation techniques reduce the need for drugs by up to 70%.

- Physical activity: Even 20 minutes of walking a day lowers agitation and improves sleep.

When Might a Doctor Still Prescribe These Drugs?

The guidelines say: only if the person is a danger to themselves or others, and all other options have failed. Even then, the goal isn’t to keep them on it forever. It’s to use the lowest dose for the shortest time - and then try to get them off. Every 3 months, doctors should ask: Can we reduce this? Can we stop it? If a doctor says, “We’ll keep giving it because it helps,” ask: Helps with what? The behavior? Or just makes it quieter? There’s a difference.What Families Should Do

If your loved one is on an antipsychotic:- Ask for a full medication review. Request a copy of their latest lab results and blood pressure logs.

- Ask: “Has anyone tried non-drug approaches? What were they?”

- Ask: “What’s the plan to get them off this drug?”

- Ask: “What signs should I watch for - like dizziness, slurred speech, weakness?”

- Don’t be afraid to say no. You have the right to refuse.

The Bottom Line

Antipsychotics don’t treat dementia. They mask symptoms - at a deadly cost. The stroke risk isn’t theoretical. It’s documented. It’s measurable. It’s real. We’ve known this for nearly 20 years. Yet, too many seniors are still being put on these drugs without consent, without alternatives, without warning. The answer isn’t more pills. It’s more time. More training. More compassion. And the courage to say: There’s a better way.Are antipsychotics ever safe for seniors with dementia?

Antipsychotics are never truly safe for seniors with dementia. All types carry a significantly increased risk of stroke and death. Guidelines from the American Geriatrics Society and the FDA strongly advise against their use for behavioral symptoms. They may be considered only in extreme cases - like when someone is physically aggressive and poses an immediate danger - and even then, only at the lowest possible dose for the shortest time, with a clear plan to stop.

Do atypical antipsychotics have fewer side effects than typical ones?

Atypical antipsychotics (like risperidone or quetiapine) cause fewer movement disorders than older typical drugs (like haloperidol). But they don’t reduce stroke or death risk. In fact, they’re more likely to cause weight gain, diabetes, and high cholesterol - which also raise stroke risk over time. Studies show both types are equally dangerous in the short term, and long-term use of typical drugs carries a slightly higher risk.

How quickly can antipsychotics cause a stroke in seniors?

Stroke risk increases within weeks - even days - of starting the drug. A major 2012 study of U.S. veterans found that the risk of stroke rose by 80% after just brief exposure. This contradicts the old belief that only long-term use was dangerous. The danger is immediate, which is why guidelines now warn against even short-term use unless absolutely necessary.

What are the alternatives to antipsychotics for managing dementia behaviors?

Non-drug approaches are proven and safer. These include reducing noise and clutter, maintaining daily routines, playing familiar music, encouraging light physical activity, and training caregivers in de-escalation techniques. One nursing home in Nova Scotia cut antipsychotic use by 60% by teaching staff to understand the person’s history and unmet needs - not just control the behavior.

Why do doctors still prescribe antipsychotics if they’re so risky?

Many doctors prescribe them because families and staff are under pressure. Agitation can be overwhelming, especially in understaffed nursing homes. There’s often no time to try non-drug methods, and no easy access to specialists. Also, some doctors believe the drugs are “necessary” - even though guidelines have warned against them since 2005. Better education and support for caregivers are needed to change this pattern.

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

Lawrence Armstrong

December 11, 2025 AT 11:58Just saw this posted in my mom’s nursing home parent group. I cried. They put her on quetiapine after one night of screaming. No one asked us. No one explained the black box warning. She had a TIA 3 weeks later. I didn’t know it could happen that fast. 😔

Donna Anderson

December 12, 2025 AT 09:30omg yes!! my grandma was on risperidone for 2 weeks and started walkin funny and fell 3 times. they said it was 'just aging' but i knew. i demanded they stop it. she’s been better ever since. no drugs = more personality. who knew?? 🙌

Rob Purvis

December 12, 2025 AT 21:51Let’s be clear: the FDA black box warning is not a suggestion-it’s a legal red flag. The fact that 1 in 5 seniors on these drugs suffer stroke or death within a year isn’t a statistical anomaly-it’s a systemic failure. And yet, nursing homes still bill Medicaid for these prescriptions as if they’re benign. The profit motive is undeniable: antipsychotics reduce staffing costs. That’s not medicine. That’s cost-cutting disguised as care.

Studies from 2012 to 2020 consistently show no meaningful difference in behavioral outcomes between drug-treated and non-drug-treated groups. The only difference? Mortality rates. We’re not treating dementia. We’re sedating it to death.

And when families are told, “It’s the only way,” they’re being gaslit. Non-pharmacological interventions work-when they’re resourced. But staffing ratios in 80% of U.S. nursing homes are below minimum safety thresholds. So the drugs become the default. Not because they’re effective. But because the system is broken.

It’s not that doctors are evil. It’s that they’re trapped in a broken system that rewards speed over safety. We need policy reform-not just awareness.

wendy b

December 14, 2025 AT 04:05Actually, the data is not as conclusive as you imply. Many studies have methodological flaws-selection bias, confounding variables, inadequate control groups. The FDA warning was based on observational data, not RCTs. And let’s not forget: untreated aggression can lead to falls, injuries, and even fatal trauma. Sometimes, the lesser evil is pharmacological intervention. You’re ignoring the complexity.

Also, “person-centered care” sounds lovely, but it requires 1:1 staffing-which doesn’t exist. You’re romanticizing an impossible ideal.

sandeep sanigarapu

December 15, 2025 AT 08:34My uncle in India was given haloperidol for dementia. He stopped eating. Could not walk. We stopped the medicine. He smiled again in 7 days. No fancy training. Just stopped the poison. People here call it 'sleeping pill for old people'. They do not know it kills.

Adam Everitt

December 16, 2025 AT 19:23It’s ironic, isn’t it? We’ve medicalized the natural unraveling of the mind-then chemically suppressed the very expressions that make a person human. We don’t want to witness decline. So we silence it. Antipsychotics are the modern equivalent of the straitjacket… but with a prescription pad. And a profit margin.

Perhaps the real dementia isn’t in the brain… but in the culture that sees dignity as optional.

Ashley Skipp

December 17, 2025 AT 03:51Why are people so dramatic about this? My aunt was on risperidone for a year and she’s fine. She sleeps better. She’s not hitting people anymore. So what if she gained 20 pounds? At least she’s not screaming at 3am. You think families want to watch their loved ones destroy themselves? Sometimes meds are the only thing keeping the peace.

Nathan Fatal

December 19, 2025 AT 03:36Let’s cut through the noise. The evidence is overwhelming. Antipsychotics kill. Period. The FDA warning is 20 years old. The American Geriatrics Society has been screaming this since 2015. And yet, 1 million seniors are still on them. This isn’t ignorance. This is negligence. Institutionalized neglect. And the people who profit from it-pharma, nursing home chains, even some doctors-are complicit.

Non-drug interventions aren’t ‘niceties.’ They’re evidence-based, cost-effective, and humane. But they require investment. And nobody wants to pay for compassion. So we pay in corpses instead.

Stop calling it ‘care.’ It’s a death sentence with a side of convenience.

Robert Webb

December 20, 2025 AT 15:49I’ve spent 12 years as a dementia care coordinator, and I’ve seen both sides. I’ve watched families break down because their mother won’t stop yelling. I’ve watched staff cry because they don’t know how to help. And I’ve watched people die because they were given a pill instead of a hug.

It’s not that we don’t know what works. It’s that we’ve built a system that punishes patience. Training staff in de-escalation? That takes time. Creating quiet rooms? That costs money. Hiring enough people? That’s not in the budget.

The Nova Scotia nursing home didn’t magically get more money. They just changed their mindset. They stopped asking, ‘How do we stop this behavior?’ and started asking, ‘What is this person trying to tell us?’ That shift-small, quiet, human-saved lives. And it didn’t require a single prescription.

So yes, antipsychotics are dangerous. But the real tragedy? We knew this all along. We just chose not to act.

Laura Weemering

December 22, 2025 AT 06:39Have you considered that this entire narrative is a distraction? Big Pharma is being scapegoated to divert attention from the real issue: the collapse of public elder care infrastructure. The real villains are the politicians who defunded nursing homes for decades. The real poison isn’t risperidone-it’s austerity. The drugs are just the symptom. The disease is capitalism.

And let’s not pretend that ‘person-centered care’ is scalable. It’s a boutique luxury for the wealthy. The rest of us get pills and silence.

Also-why is no one talking about how the FDA’s black box warning was pushed by the same agencies that approved SSRIs for kids? Hypocrisy is the only consistent policy here.

Audrey Crothers

December 23, 2025 AT 05:49My grandma went from screaming at the TV to singing along to Sinatra in 48 hours after they took her off quetiapine. We started playing her old records, holding her hand, just… being there. No meds. No chaos. Just love. 💖 It’s not magic. It’s just… human. Why is that so hard to do?

Stacy Foster

December 24, 2025 AT 04:39THIS IS A GOVERNMENT PLOT. They want old people dead so they can save Social Security money. The FDA, pharma, nursing homes-they’re all connected. They’ve been lying since 1998. They’re using antipsychotics to cull the elderly population. Watch the news-they never report the deaths. They call them ‘natural causes.’ It’s genocide with a prescription.

Reshma Sinha

December 25, 2025 AT 22:26As a geriatric nurse in Delhi, I can confirm: antipsychotics are overprescribed globally. In low-resource settings, we use them because we have no behavioral therapists, no occupational therapy, no trained aides. It’s not malice-it’s survival. But we must advocate for training, funding, and policy change. We cannot normalize chemical restraint.

Levi Cooper

December 26, 2025 AT 18:49Why are we letting foreigners tell us how to care for our elders? In America, we’ve always respected our seniors. This ‘non-drug’ nonsense sounds like European socialism. We need more security, not more hugs. If someone’s violent, they need to be calmed down. That’s common sense.

nikki yamashita

December 27, 2025 AT 12:33My dad’s on quetiapine. I’m going to ask for a review this week. Thank you for this. I didn’t know I could say no.

Nathan Fatal

December 27, 2025 AT 13:53Exactly. You have the right to refuse. And if they push back, ask for the consent form. If they can’t show you the signed document where risks were explained? That’s medical malpractice. Document everything. And if they say, ‘It’s for her safety’-ask: ‘Whose safety? Hers? Or yours?’